The archaeological excavation and its museum

One of the Acropolis Museum peculiarities is that it has incorporated in its architectural design the ruins of the ancient neighbourhood that were brought to light during the archaeological excavation conducted for the Museum’s construction. These ruins, visible through the glass floor and the Museum’s balconies, converse with the masterpieces of the ancient Greek civilisation that are exhibited in its galleries.

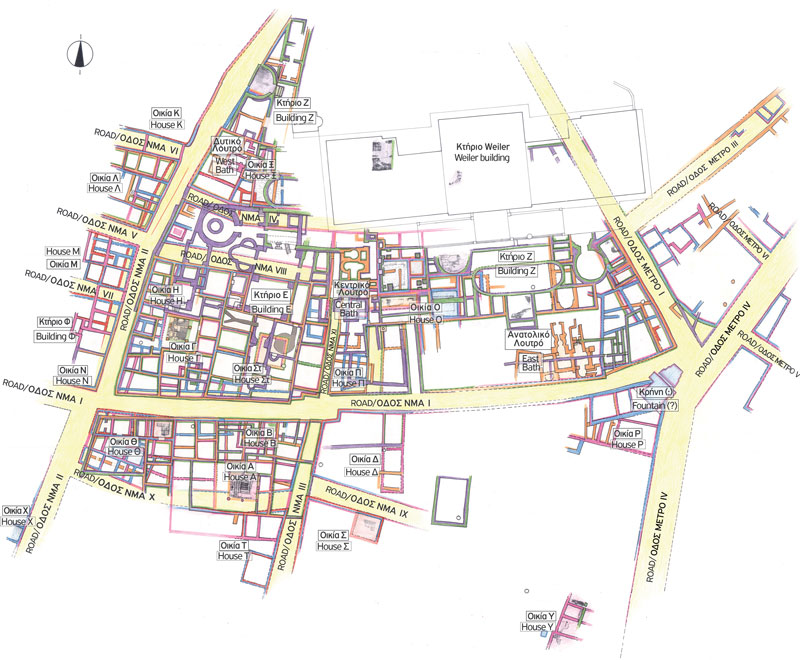

The excavation was opened to the public in June of 2019, offering to the visitors the possibility to get to know the ancient neighbourhood. To walk on its streets; check out the houses with the courtyards and the wells; enter the heart of the impressive mansions with the private baths; observe the workshops with their water cisterns, in other words take a journey through time, history and daily life of the people who lived here, in the Acropolis’ rock shadow, from the 4th millennium BC until the 12th cent. AD.

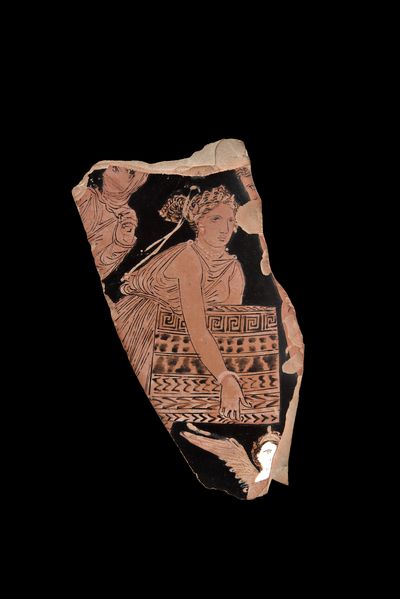

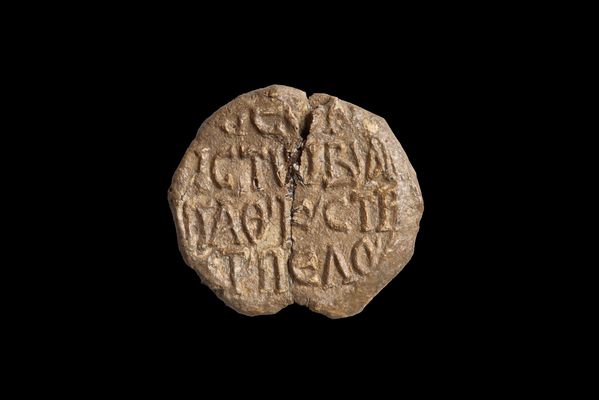

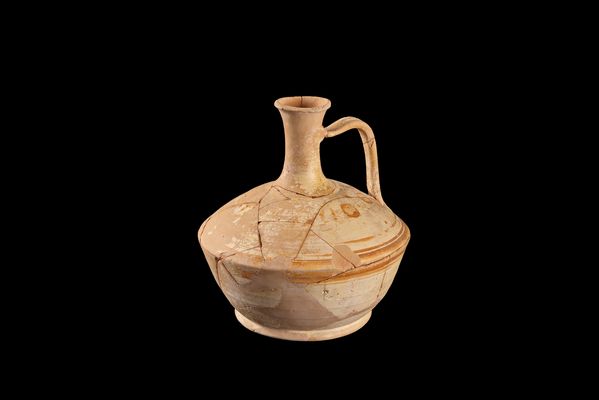

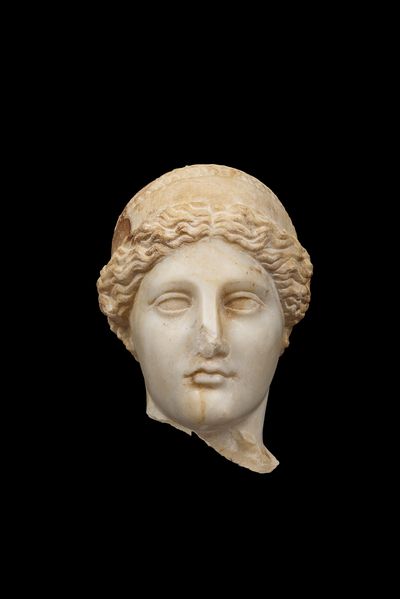

This journey is completed with the small “Museum of the Excavation” that was inaugurated in June of 2024. Organised in the southern edge of the excavation –next to the ruins of the ancient neighbourhood- it presents part of the objects left behind by the people who were born, lived and created in this corner of ancient Athens.

Brief history of the Makrigiannis plot

Human activity first appears on the site somewhere between 3,500 and 3,000 BC. Until the 9th cent. BC, houses, workshops and cemeteries coexist or succeed one another. Though sparse, the residential use of the site begins to form from the middle of the 8th cent. BC. Until the beginning of the 5th cent. BC, the area stands on the outskirts of the city, outside its old fortification walls.

A major change takes place at the end of the 5th cent. BC, when the district becomes more organized, finally acquiring its urban character and becoming incorporated within the city walls. By the beginning of the 1st cent. BC, a dense street network develops and the site is occupied by houses with small internal courtyards, as well as shops and workshops. In 86 BC, the neighbourhood is destroyed by the Roman general Sulla’s troops, then left abandoned for several years. Soon thereafter, industrial units are established on top of the ruins.

From the mid-2nd cent. AD, however, the district experiences a new boom. The houses are now larger. Most of them acquire colonnaded courtyards; rooms with multicolor frescoes and even occasionally mosaic floors; private latrines; and, in the most luxurious residences, their own private baths. Prosperity comes to an abrupt halt in AD 267, when the Herulians, a Germanic tribe of the North, ravage the city of Athens and destroy the site.

Following the site’s further reorganization in the late 4th-early 5th cent. AD, all the houses have colonnaded courtyards, although their character and dimensions vary. Adjacent to smaller houses, possibly belonging to middle-class people, larger, more luxurious structures arise, constituting the urban villas of affluent citizens.

By about the mid-5th cent. AD, most residences are repaired and continue to function. At the same time, two properties containing villas are taken over by a single luxurious residence (Building Z) featuring mosaic floors and a private bath – the seat of a high-ranking official or local aristocrat with ties to the imperial court.

At the beginning of the next century, Building Z acquires a new wing (Building E) with elements that are architecturally innovative for Athens. This building, in combination with other restored or newly erected houses, indicates the continuity of urban life during a period when Athens is considered to suffer decline and urban shrinkage.

At the end of the 6th cent. AD, some buildings are destroyed and others damaged. In the lower level of Building E, workshops are established, operating until at least the start of the 8th cent. Later, they are abandoned and for several years the area stands deserted. New houses and workshops develop during the 10th through 12th cents. AD, which function until the site’s final abandonment in the early 13th cent. AD.

At the beginning of the 19th cent., on top of the ruins of Building Z, the first military hospital of the city of Athens is erected, known as the “Weiler Building”. Today, this building houses the Acropolis Museum’s administrative offices.